Discovering how a reduced or altered likeness can carry deep meaning starts with two pulls: the brain’s habit of finding faces and the heart’s urge to attribute feeling.

This brief guide explores how art sits between pareidolia and empathy, and why that balance matters for viewers, collectors, and makers today.

Expect clear answers about whether portraits can be non-literal, practical rules for painting, and a simple breakdown of the six key elements that shape abstract work.

We trace a line from the 16th-century hierarchy of genres to modernists who broke those rules, and name pioneers like Malevich, Mondrian, and Gabo to ground theory in real practice.

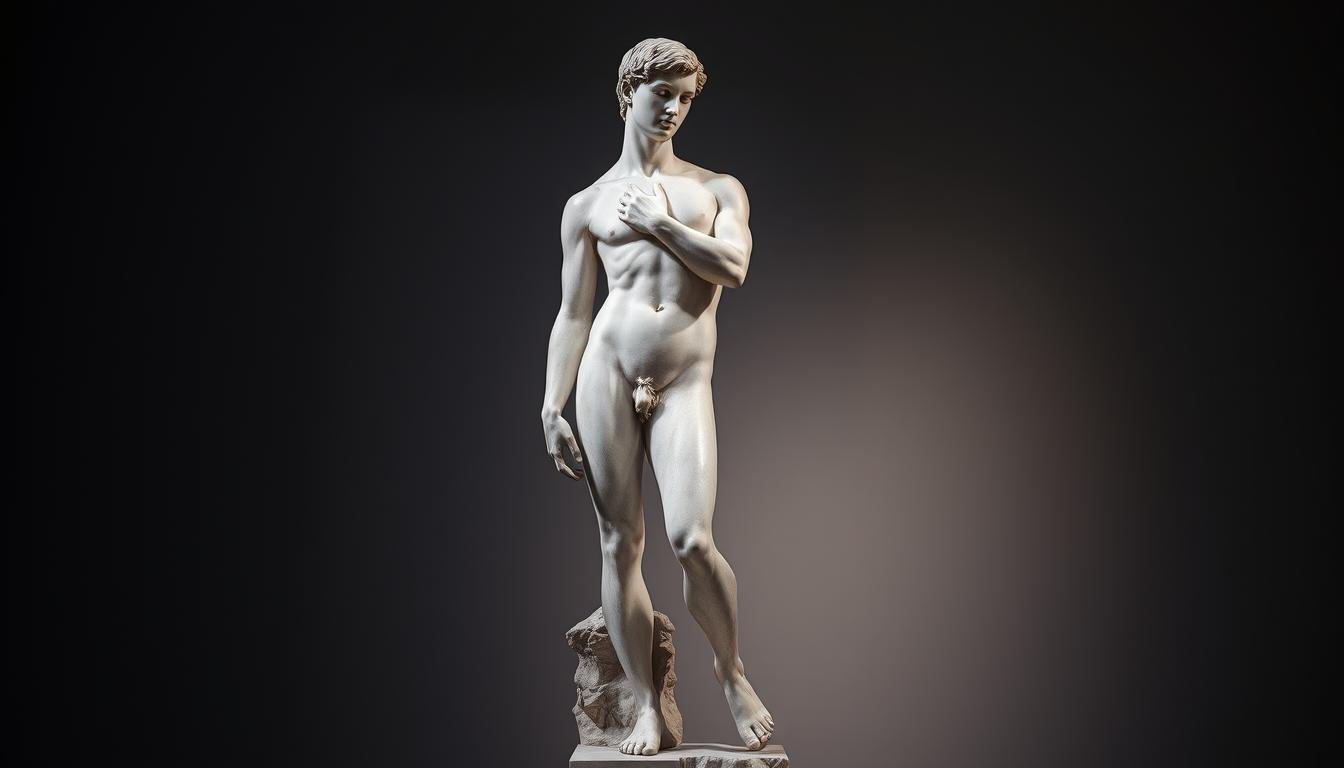

Across painting, sculpture, photography, installation, and performance, likeness may recede while identity intensifies through color, form, and structure. Read on to learn how to separate first impressions from deeper readings and to see or make better portraits in today’s vibrant art world.

Key Takeaways

- Abstract portraits blend cognitive face recognition with emotional projection.

- They appear in many media, not just painting.

- Modern artists challenged old genre rules to expand portrait purpose.

- The guide answers whether portraits can be non-literal and offers practical painting rules.

- Six core elements give a clear method to evaluate abstract works.

What is an abstract portrait?

Some images suggest a presence without naming it, leaving viewers to fill in identity from cues. In this sense, a work counts as portraiture when it intends to represent a subject while choosing idea over exact likeness.

Defining portraiture beyond likeness: figure, face, and the realm of ideas

Artists may hint at afigureor afacethrough color, repeated signs, or simplifiedforms. The sitter can be human, animal, mythic, or hybrid. What matters is the intention to portray someone or something, not a fixed visual formula.

Abstract vs. representational portraiture: how meaning shifts for the viewer

Unlike representational work that mirrors features, abstract art reshapes elements to suggest inner life, concept, or mood. Simplifying, schematizing, or distorting can still convey identity and presence even when recognition fails.

Tip: Look for titles, motifs, and repeating marks to confirm portrait intent before judging the message. Across media—painting, photography, sculpture, installation, performance—the treatment of subject and the maker’s intent define the result.

Can portraits be abstract? Short answer and why it matters

Yes — portraits can go fully into idea-driven form while still claiming to represent someone.

Such works may be paintings, photographs, sculpture, installation, or performance that suggest a being or its qualities while focusing on ideas rather than faithful likeness.

This matters because abstraction lets artists capture time, culture, and psychological states that a mirror image often cannot. It frees a maker to prioritize symbol, mood, or social comment over surface detail.

Viewers approach these pieces differently. Without instant recognition they weigh composition, color, and title to find meaning. Pareidolia and empathy both guide and complicate that search.

Collectors care too: assessing intent, coherence, and innovation matters more than technical resemblance when the market values concept and risk-taking.

Remember: this is a spectrum. Many works sit between likeness and full reduction. Knowing where a piece lands clarifies its goals and enriches how we read its art approach.

The evolution of abstraction in art

A wave of painters and sculptors around 1907 rewired representation, giving rise to visual systems that spoke through form and color.

Cubism fractured space and broke objects into planes. That move loosened the need for single viewpoints.

Fauvism pushed color toward emotional force. Bright, nonnatural hues made color a carrier of meaning.

These shifts let artists take a further step: removing direct reference to the visible world and crafting a new visual language.

From Cubism and Fauvism to “pure” abstraction

By 1910–1920 some painters stopped naming things. Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian led the turn to geometry and balance. Their work made order and purity the painting’s subject.

Malevich, Mondrian, and Gabo: refining non-objective language

Malevich and Mondrian codified rules: simple shapes, clear relationships, and visual harmony carried meaning without figures.

Naum Gabo translated similar ideas into sculpture. He used modern materials and open structure so form could imply thought rather than mimic flesh.

- Early movements broke depiction into new parts.

- Non-objective painters favored geometry and balance.

- Sculptors used structure and material to suggest ideas.

Why it matters: these developments gave artists tools to build portraits as systems of color, shape, and symbol rather than copies of faces. For historical context see history of abstract art.

Abstract portraits in art history and practice

When avant-garde makers rejected academic order, they opened portrait practice to new subjects and media. This shift began as a challenge to rules set in the 16th century and grew into a broader cultural change.

Breaking the hierarchy of subject matter from the 16th century onward

Renaissance taste treated grand narratives as top-tier subject matter, while likeness-based images retained prestige but stayed tied to status display. Typical works emphasized realistic head-and-torso views and clear social cues.

Modern movements upended that logic. Artists widened the frame, treating whole bodies, faces, animals, and symbolic signs as valid subjects. Paintings, photography, sculpture, installation, and performance all carried portrait intent into new forms.

By reframing goals, makers focused less on who sat for the work and more on what traits, relationships, or ideas were under examination. That change also meant the marginalized could appear with dignity and complexity.

Today, many creators prioritize concept, process, or social context over strict resemblance. This history explains why contemporary practice prizes experimentation across media and meaning over mere mimicry.

Abstract portrait vs. abstract art: where they intersect

A single canvas can either trace a life or explore pure form; the clue sits in intent and signal.

All abstract portraits are a type of abstract art, but not every work of abstract art points to a being. A piece becomes portrait when visual choices link to identity, biography, or a named sitter rather than existing only as formal play.

Look for facial cues, titles that name a person, recurring motifs tied to a life, or biographical symbols. Those elements signal portrait intent even when the image breaks down into simple forms.

Artists often translate features into angles, arcs, or color fields that stand for presence or character. These shorthand moves point away from literal reality and toward expressive matter.

Many works sit between the poles. Context—exhibition notes, series titles, or an artist statement—usually reveals whether identity was the goal.

Quick reading strategy: first search for signs of intent; second, judge how the abstract choices build a narrative of identity. That approach helps viewers and collectors place a work accurately in a collection or in critical discussion.

| Feature | abstract art | abstract portrait | How to tell |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Purely formal or invented | Rooted in a person or identity | Check titles and motifs |

| Signs | Emphasis on shape and color | Facial cues, props, biography | Look for repeated, personal markers |

| Intent | Focus on material and idea | Claims to represent someone | Read artist notes or series context |

| Collection use | Decorative or conceptual display | Biographical or curatorial focus | Place by narrative relevance |

The psychology of seeing faces: pareidolia and empathy

Perception supplies faces from fragments, and that habit shapes how we meet reduced or suggestive images. This section helps a reader notice automatic reactions and read work more clearly.

When we see faces in everything: benefits and pitfalls

Pareidolia names the mind’s tendency to find a face from minimal cues. Artists use this to suggest personhood with just a few marks.

That shortcut can also mislead. A viewer may fixate on imagined features and miss color, composition, or the underlying idea the maker set up.

Empathy’s double edge: connection and bias

Empathy deepens engagement: we feel toward a perceived sitter and assign emotions quickly. Yet empathy can import bias or fear, especially with works that touch on gender or marginality.

How these forces shape the viewer’s experience

“Notice the first face you see, then ask whether feeling or design leads your response.”

Try this habit: name the first face you find, step back, then read rhythm, color, and structure. Doing so lets emotions inform rather than override judgment.

- Acknowledge your first impression.

- Check formal choices next.

- Return once more to test if your reaction was about the work or your own mind.

What are the rules for abstract painting?

Make the first mark with purpose: commit to one idea and let that idea steer every choice. This Rule of Intent keeps emotion, identity, rhythm, or structure central so the work reads clearly.

Rule of simplification

Reduce, schematize, or distort forms to highlight essentials. Remove anything that does not serve the concept. For portraits, keep one repeated cue—title, motif, or mark—to keep identity legible without literal depiction.

Rule of coherence

Build internal order through consistent rhythm, scale, and spacing so the image feels inevitable. A sense of order makes surprising moves feel deliberate rather than accidental.

Rule of material honesty

Let brushwork, lines, edges, and surface gestures speak. Avoid over-polishing; the energy of the mark often carries the painting’s conviction.

- Iterate: after each session, test whether the canvas still expresses the original idea.

- Measurable checks: squint for value, flip the work, and try thumbnails before large moves.

- Rules are tools—break one on purpose and ensure the result strengthens the idea.

The six elements of abstract art

To read a non-literal image well, break it into specific elements and test each on its own. Below are six practical tools artists use to suggest identity without copying a face.

Line and gesture: energy and direction

Lines and quick gestures set motion and attitude. A bold sweep can read as confidence; a hesitant mark reads as doubt. Vary pressure and speed to encode tempo and intent.

Color: harmony, contrast, and emotional charge

Color works through temperature, saturation, and contrast. Warm, saturated fields push forward; cool, muted tones recede. Complementary pairings heighten tension while analogous schemes soothe mood.

Shape and form: geometric, organic, and hybrid structures

Shapes and forms give bodies to ideas. Geometric blocks imply order or mask, while organic curves suggest flesh or emotion. Hybrid structures can hint at anatomy without literal depiction.

Texture and surface: material presence

Texture signals touch and history. Impasto adds weight and time; glazing creates depth; dry media suggest fragility. Surface choices tell viewers how to feel the image.

Space and composition: balance and tension

Space organizes priority. Use value, edge contrast, or clustering to create a focal point. Balance keeps the image coherent; deliberate tension guides the eye and the reading.

Idea and symbolism: the conceptual backbone

Motifs, repeated marks, or symbolic signs anchor intent. Let one strong motif carry narrative and let other elements support or contrast it so the work holds together as a whole.

- Quick tip: if one element shouts, tune the others to harmonize or intentionally counterpoint it to avoid chaos.

- Analyze by isolating each element, then recombine to judge the overall effect.

How abstract portraits communicate identity

Artists often signal identity through repeatable forms rather than facial detail. Small, recurring shapes or a favored color family act like a signature. Over time these markers point to a figure or persona without mapping features.

Titles, series logic, and motifs help readers connect concept and sitter. A title can name a role; a series can show variation. Reused symbols tie separate works into a coherent identity language.

Identity can also be relational. The bond between maker and subject shows up in scale, rhythm, or tension. Work may reference cultural narratives, history, or a personal rapport rather than likeness.

“A restrained palette suggests reserve; explosive gesture projects vitality.”

- Look for pattern consistency across an artist’s body of work.

- Notice how form, color, and composition repeat or evolve.

- Read layers: memory, role, and emotion often underlie visual choice.

In short: formal decisions—rhythm, motif, and palette—carry identity as surely as a face does in traditional portraiture.

Pablo Picasso to Willem de Kooning: abstraction and the face

Two mid-century giants remade the face by turning gesture and geometry into expressive tools.

Picasso’s language of forms: from analytic to synthetic

pablo picasso used analytic Cubism to break faces into planes, then synthetic moves to recombine signs and color.

In The Dream he pushes curves and surface toward erotic suggestion. Some viewers read sexual symbols; others see sculpted rhythm. Pareidolia and empathy help explain why narratives appear in ambiguous shapes.

De Kooning’s Women: gesture, power, and contested readings

willem kooning painted with forceful strokes and many revisions. His Women series reads as charged, even hostile to some, while his abstract landscapes win praise for lyricism.

This contrast shows how subject cues change reception. Both makers aimed for invention and often humor, not literal insult.

- Read structure first: note composition, color, and rhythm before narrative.

- Separate intent from reaction: consider artist statements and series context.

Case studies like these remind readers that viewer bias shapes meaning in art.

Paul Klee and Robert Delaunay: color, order, and the figure

Two paths—geometric order and divisionist color—show how painters translated identity into formal rules.

Paul Klee used simple geometry and measured balance to suggest a sitter’s temperament. Senecio (1922) reduces a face to planes and calibrated tones so that pose and poise read through structure rather than detail.

Klee’s language of proportion and hue turns the canvas into a quiet study of inner poise. The result reads like a meditation: identity arrives by way of arrangement, not mimicry.

Divisionist vibration and surface focus

Robert Delaunay experimented with juxtaposed hues in his early portrait of Jean Metzinger (1906). Small color units create optical vibration, and the flattened picture plane refuses modeled depth.

That flatness directs attention to surface interactions. Here, the sitter’s presence comes from color logic and compositional clarity rather than a sculpted likeness.

Together, these artists show how formal choice communicates intent. Track color decisions across a series to see how painters build a private language that makes identity legible through order and hue.

Abstract portrait photography and beyond

Lens-based work often pushes portraiture into idea-first territory, testing whether an image can hold competing truths.

Man Ray’s Noire et Blanche: reality versus visage

Man Ray pairs a sitter’s face with a wooden mask to unsettle our trust in visible reality. The side-by-side compares flesh and object so we must decide which reads as true.

Duchamp’s double image: combined realities

Victor Obsatz’s 1953 double image of Marcel Duchamp overlays a calm profile with a grinning frontal view. That single frame compresses time and emotion, making character feel like a constructed collage of selves.

From painting to sculpture and performance: portraiture across media

These strategies move easily into sculpture, where form, material, and negative space imply presence without literal likeness. Performance and installation extend the idea so identity is acted, staged, or shared with an audience.

Look for titles, juxtaposition, and montage in lens-based images; they work as abstract tools to signal intent. Across media, the aim stays the same: to show identity as layered and made, inviting active interpretation rather than simple recognition.

Interpreting abstract portraits without bias

Treat the canvas as evidence: inventory composition, color, rhythm, and structure before you name a sitter. This neutral read helps a viewer separate immediate emotion from observable choices.

Record what the work shows and what it reminds you of, then give priority to the piece’s own ideas. Note that depictions of women often trigger different vocabularies; stay alert to loaded words and replace them with descriptive terms tied to marks, scale, and hue.

Cross-check your notes with context: title, series, and date anchor meaning. Reflect on any discomfort you feel — treat that as information about you, not proof about the painting. Revisit the work after each check.

Use a three-pass habit: formal read, conceptual read, then integrated read.

- Formal read: list shapes, edges, and balance.

- Conceptual read: ask what themes or social cues appear.

- Integrated read: combine facts and sense to form a fair, aligned interpretation.

This approach keeps art readings rigorous and kinder to intent while giving viewers a clearer path to meaningful judgment.

Building an abstract portrait: from concept to composition

Begin with a clear idea: name who you intend to portray and why a reduced approach better serves that story. Keep this concept statement short and refer to it during every decision.

Choosing subject matter and degree of abstraction

Decide how many clues the image will give. Place your work on a continuum between hint and likeness.

Choose a single motif or repeated emblem that will anchor recognition. Use titles and context to reinforce intent when visual cues grow spare.

Mapping elements: lines, shapes, color, and space

Make quick studies to test how lines direct attention and how shapes build form. Use small thumbnails to lock hierarchy before large moves.

- Start: write a one-sentence concept.

- Plan: sketch value and color thumbnails to set focus.

- Check: confirm the motif or emblem keeps the sitter legible.

- Refine: let accidental texture stay only if it serves the idea; erase clutter.

- Finish: remove redundancy so the image reads as inevitable.

Tip: iterate with short pauses. Use empathy and pareidolia to cue connection, but keep formal choices in balance so the final piece functions clearly as art.

Viewing strategies for audiences and collectors

Start any careful viewing by treating the canvas as a system of choices rather than a riddle to solve.

Look past recognition: read formal choices first

First pass: scan structure and rhythm. Note major shapes, balance, and focal points before naming anyone. This step helps the viewer separate design from story.

Second pass: check color, edges, and value. Ask how these choices steer the eye and set mood. Postpone identity guesses until you finish this read.

Track your own empathy and assumptions

Keep a short journal. Record your first impression, then write a formal note. Comparing both entries exposes assumptions and reveals whether feeling or evidence drives your response.

“List what the work does, then decide what it means.”

- Scan composition, then color and edges.

- Look for symbolic cues last; titles and series often confirm intent.

- For collectors: check consistency across a series, read the artist’s statement, and test whether the image keeps working after repeat viewings.

- Compare multiple images in the same show to benchmark depth and craft.

| Step | Action | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Structure & rhythm | Reveals the work’s backbone |

| 2 | Color & edges | Sets mood and focus |

| 3 | Symbolic cues | Anchors identity and narrative |

Remember: changing your mind after a second look is good. Patience often rewards the viewer with clearer sense and richer appreciation of the art.

Keywords and themes in today’s abstract portraiture

Artists now borrow staging, performance, and montage to extend portrait language beyond a single frame.

Contemporary practice blends conceptual clarity with cross-media play. Many abstract portraits layer selves, histories, and public roles so a work can hold several meanings at once.

Recurring themes include multiplicity of self, cultural hybridity, and the pull between private life and public display. Social currents—visibility, marginalization, and empowerment—often appear as coded color or repeated structural motifs.

- Cross-disciplinary moves: installation staging, performance gesture, and photographic montage expand how portraits communicate.

- Artists use signature forms, materials, or processes so identity reads across a series.

- Compact vocabulary to use: hybridity, layering, non-objective signaling, symbolic anchoring.

For readers and collectors, track how motifs recur across shows. Follow exhibitions and journals that focus on portraiture to see how these trends evolve in the contemporary art world.

Conclusion

In short, the final pages bring practice and history together so you can read images with care and curiosity.

Yes: portraits can go non-literal. Across modern and contemporary work, makers use reduction to press form into meaning rather than erase presence.

Follow a few clear rules: name intent, simplify forms, keep internal order, and let material speak. Use the six elements — line, color, shape, texture, space, and idea — as a compact toolkit.

From pablo picasso and willem kooning to Klee and Delaunay, artists showed how energy, order, and color remap the face. Try this across painting, sculpture, and images: pause, read forms and color relationships, then let the work reveal deeper identity beyond surface reality.

Enhance Your Space with Unique Modern Masterpieces

Are you inspired by the innovative mediums and conceptual depth highlighted in our exploration of contemporary art? You’re not alone! Today’s art enthusiasts are seeking cultural relevance and emotional connections in their artwork. However, finding pieces that resonate with modern themes and fit your unique style can be a challenge. That’s where we come in!

At Rossetti Art, we specialize in canvas prints, original paintings, and modern sculptures that celebrate the spirit of now. Each piece created by Chiara Rossetti brings a personal touch that connects deeply with current social narratives—just like the modern masterpieces discussed in the article. Don’t miss out on the chance to elevate your home decor with breathtaking artwork that speaks to your values and aesthetic. Explore our collection today and find your perfect piece! Act now, and transform your space into a gallery of inspiration!

FAQ

What does an abstract portrait mean in art?

It strips away photographic likeness to explore face, figure, and identity through shapes, color, and gesture. Artists use distortion, simplification, or symbolic elements to suggest personality, emotion, or social role rather than reproduce exact features.

How does abstract portraiture differ from representational portraiture?

Representational work aims for likeness and surface detail. Abstract approaches prioritize idea, mood, and formal choices — line, plane, and color — so the viewer responds to composition and concept before literal recognition.

Can portraits be abstract and still read as faces?

Yes. Pareidolia helps viewers find face-like patterns in minimal cues. Skilled makers balance suggestion and ambiguity so a composition reads as a person while remaining open to interpretation.

How did abstraction evolve in portraiture?

Movements like Cubism and Fauvism loosened the hold of strict likeness. Later experiments by modernists expanded non-objective language, allowing portraiture to borrow geometry, color theory, and material honesty from broader abstraction.

Which artists matter for the history of abstract faces?

Pablo Picasso reworked the plane and perspective of the face; Willem de Kooning pushed gesture and figuration; Paul Klee and Robert Delaunay explored color, rhythm, and simplified form. Each shifted how identity could be signaled without exact depiction.

What rules guide abstract painting focused on people?

Key principles include clear intent, simplification of form, coherence in visual logic, and material honesty. These keep the work readable and emotionally resonant rather than arbitrary.

What elements make up strong abstract work?

Line and gesture, color, shape and form, texture, space and composition, and underlying idea or symbolism form the backbone. Together they create balance, tension, and meaning.

How do abstract portraits communicate identity?

Through choices in scale, palette, distortion, and mark-making that suggest temperament, history, or role. Viewers infer character from formal signals rather than photographic detail.

How has photography influenced abstract portraiture?

Photographers such as Man Ray experimented with collage, light, and double exposure to challenge appearance. Photographic techniques informed painters and sculptors exploring fragmentation, montage, and altered reality.

How can viewers avoid bias when interpreting abstract faces?

Focus on formal language first — color, rhythm, and composition — then consider emotional response. Be mindful of cultural assumptions and let the work’s structure guide meaning rather than immediate recognition.

What practical steps help build an abstract portrait?

Start with a concept for identity or mood, choose how much to reduce or distort, map key marks and shapes, and test color relationships. Maintain internal coherence so gestures and forms support your idea.

What should collectors look for when buying abstract portraits?

Assess composition, material quality, and the clarity of the artist’s intent. Consider how the work resonates emotionally and whether the formal language holds up beyond surface novelty.

Which themes dominate contemporary abstract portraiture?

Identity, memory, race, gender, and the body frequently recur. Artists blend figuration and non-objective elements to address politics, psychology, and personal narrative through shape and color.

How do sculptors and performers approach abstract faces?

Sculpture emphasizes material presence and form in three dimensions, while performance uses movement, costume, and gesture to suggest persona. Both expand portraiture beyond painted surfaces into lived experience.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.