Have you ever wondered whether a single label can hold centuries of practice, struggle, and expression? This entry gives a clear, friendly definition used by artists, curators, and historians today.

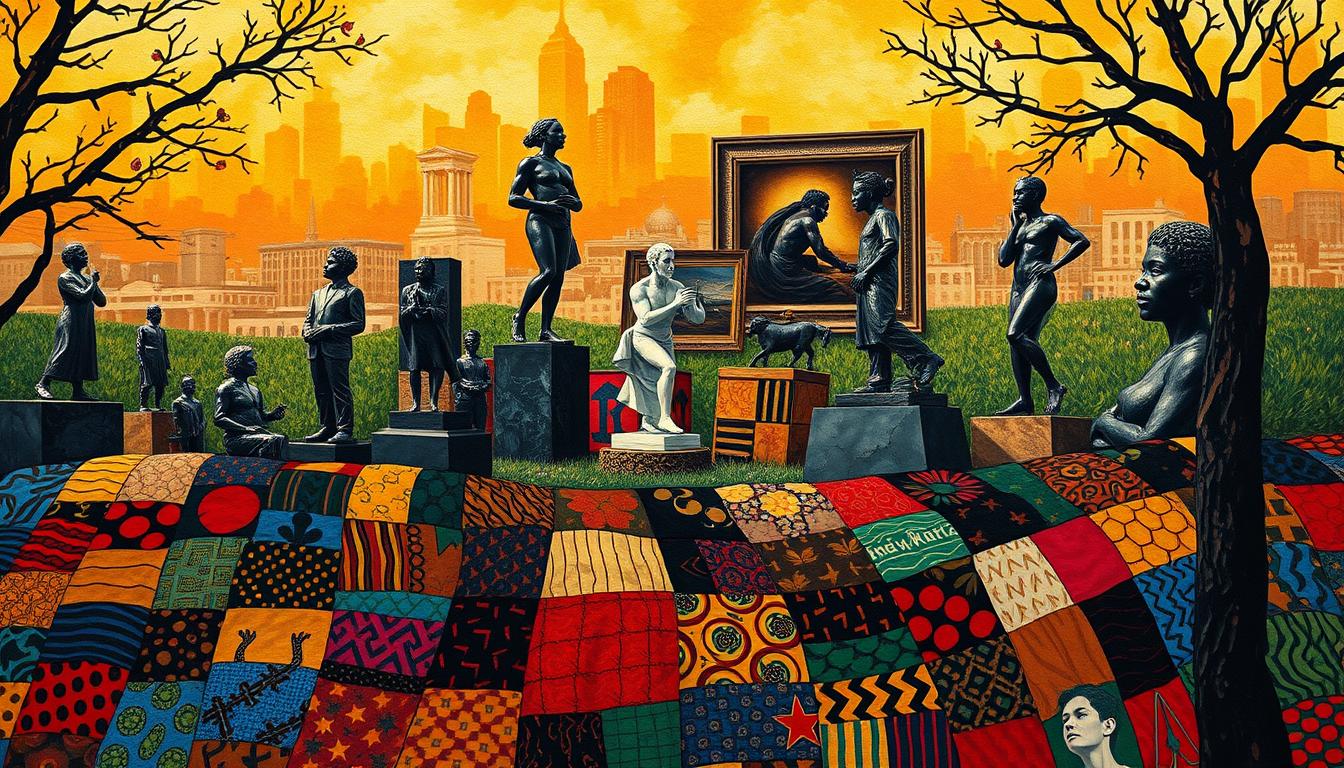

African-American art covers work made over two centuries across painting, sculpture, printmaking, quilts, and mixed media. It draws on African roots, folk techniques like quilting and basket weaving, European training, and U.S. movements such as the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement.

We offer concise definitions and vivid examples, from Edmonia Lewis and Henry Ossawa Tanner to Jacob Lawrence and Faith Ringgold. The text shows how labels shift with history, and why simple words can both help and limit understanding.

Key Takeaways

- Term links creators, themes, and community histories.

- Practice spans many media and generations.

- Labels evolve with politics and museum contexts.

- Examples clarify meaning more than theory alone.

- Definitions aim for precision while honoring breadth.

- Readers will see how usage shifts over time.

What do you call Black art? A clear glossary definition

Start with a working definition that links subject, context, and maker.

Core meaning: black art names creative work that explicitly engages Black histories, cultures, and lived experience. It often comes from Black makers, but the label centers the work’s themes and references rather than biography alone.

Term versus label

Calling a piece Black work because the artist is Black is not the same as calling it Black work because the content addresses Black life. Scholars stress that landscapes or abstracts by Black makers are not automatically within this category if they do not speak to those themes.

Related terms in use

Related entries—African-American art, the Black Arts Movement, and diaspora art—help place the term in time and place. During the Black Power era, many artists reclaimed the word as a political and cultural claim.

- Look for narrative themes, iconography, or strategies tied to Black life.

- Curators in New York often balance identity and content to avoid reductive labels.

- Use the term as a working tool in scholarship and curation, allowing for flexibility.

The short takeaway: treat the word as descriptive of intent and content, not as a default tag based only on an artist’s biography. Clear definitions help scholars and museums write more precise labels and catalogues.

From past to present: how the definition evolved in the United States

Across two centuries, artists moved from accepted European styles toward voices that named their own experience.

Early roots to the Renaissance era

In the 1800s many makers like Edward Mitchell Bannister, Robert S. Duncanson, and Joshua Johnson trained in European modes. They often worked in portrait and landscape commissions that matched mainstream taste.

Edmonia Lewis used neoclassical sculpture to weave subtle race themes. Henry Ossawa Tanner blended genre scenes and luminous technique to earn international acclaim with works such as The Banjo Lesson.

WPA, murals, and the rise of cultural power

During the 1930s, WPA support kept many makers working and visible. Jacob Lawrence, Dox Thrash, and others contributed to Social Realism, printmaking, and public murals.

The mid-century shift toward the Black Power era saw the Black Arts Movement embrace community-focused practice. Murals and local organizations reframed the field as a tool for civic engagement.

| Era | Notable Figures | Key Shift |

|---|---|---|

| 19th century | Bannister, Duncanson, Johnson | Academic training; mainstream commissions |

| Early 20th c. | Aaron Douglas, Augusta Savage, Jacob Lawrence | Harlem Renaissance; a new generation of voices |

| 1930s–1960s | Jacob Lawrence, Dox Thrash | WPA support; Social Realism and murals |

| 1960s–1970s | Community artists, Black Arts Movement participants | Political emphasis; local cultural power |

What do you call Black art? Usage in museums, media, and everyday words

Exhibitions, press coverage, and label copy together steer public understanding of these works.

Curators in major New York art museum spaces set the tone for how a work is presented. They decide when to foreground an artist’s identity and when to emphasize themes or technique. Clear labels help visitors read complex histories without reducing work to a single category.

Major reviews, including pieces in the new york times, can amplify or challenge those choices. A well-placed review reframes a show so readers think about content, context, and lineage rather than only biography.

- Placement matters: MoMA’s decision to hang Faith Ringgold’s Die opposite Les Demoiselles d’Avignon provoked new comparisons and questions.

- Artists such as Emory Douglas, Fred Wilson, and Kehinde Wiley shape how public words around these genres develop.

- Thoughtful curation resists grouping by identity alone and highlights shared strategies, media, or themes.

"Display choices can reinforce or disrupt received narratives."

When museums, critics, and educators use precise language, audiences leave better equipped to discuss meaning with nuance.

Media, styles, and themes commonly associated with Black art

Across media, makers translate memory and movement into visual languages that speak to communities.

Common media include painting, printmaking, collage, assemblage, sculpture, textile, photography, and conceptual installation. These forms reflect the full range of contemporary practice.

Styles run from Realism and Modernism to Abstract Expressionism and Conceptual work. Artists like Norman Lewis, Howardena Pindell, and McArthur Binion reshape abstraction while keeping cultural context visible.

Narrative cycles such as Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series make history painting a visual record of movement and labor. Political graphics by Emory Douglas use bold composition and text to spread community power.

Institutional critique from figures like Fred Wilson exposes how museums shape memory. Textile traditions—from Faith Ringgold’s story quilts to Gee’s Bend—link making to place and family memory.

- Sculpture spans neoclassical forms to monumental public works across New York and beyond.

- In day-to-day viewing, recurring themes include identity, joy, migration, spirituality, and social justice.

- Abstract pieces often use material, title, and context to signal cultural reference points.

"Look for layered iconography—musical motifs, vernacular objects, and historical portraits that deepen meaning."

Examples and generations: artists, movements, and collections to know

A short guide to sculpture, painting, and political work shows how examples travel between local and national collections.

Sculpture highlights: Edmonia Lewis combined neoclassical form with abolitionist themes and sold works in 1865 to fund travel to Europe. Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller mixed symbolism and realism, trained under Henry Ossawa Tanner, and earned federal commissions.

Augusta Savage’s Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp) was a landmark New York commission for the 1939 World’s Fair. Richard Hunt’s public practice includes over 160 commissions across the United States.

Painting and printmaking

Henry Ossawa Tanner trained with Thomas Eakins, painted The Banjo Lesson, and received honors from the National Academy and France’s Legion of Honor.

Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series spans 60 panels, while Faith Ringgold fused painting and quilt narratives; her Die hung opposite Picasso at MoMA in New York. Elizabeth Catlett honored everyday strength and civic heroes in sculpture and print.

Conceptual and political practices

Emory Douglas’s graphics shaped community newspapers and posters for the Black Panther Party. Fred Wilson’s installations reframe museum objects to expose hidden histories.

"These generations show how tactics move from studio practice into public life."

| Category | Notable Names | Collection Types |

|---|---|---|

| Sculpture | Edmonia Lewis, Augusta Savage, Richard Hunt, Meta V. W. Fuller | Public commissions, museum holdings, fair installations |

| Painting & Printmaking | Henry O. Tanner, Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold, Elizabeth Catlett | Gallery collections, university museums, study collections |

| Conceptual/Political | Emory Douglas, Fred Wilson | Community archives, contemporary shows, museum interventions |

Look for shows that weave sculpture, painting, and conceptual projects across a single generation and beyond. When visiting an art museum, consult collection highlights to place each maker in context.

Words and definitions: how dictionaries and art history frame the term

Reference entries offer a starting point, but usage shifts once the phrase enters galleries, classrooms, and reviews.

Dictionary usage note: entry versus context

The dictionary confirms the phrase as a recognized entry, yet the meaning changes with setting and speaker. A short lexicon line cannot capture the term’s political history or how communities reclaim it.

Art history adds crucial nuance. Scholars distinguish between works by Black makers and works that explicitly engage Black experience. That distinction helps avoid sloppy labeling and honors the maker’s intent.

- The dictionary entry establishes a basic word form and common usage.

- Curators and teachers use clear definitions to set expectations in catalogues and syllabi.

- Reviews in the new york times and other outlets shape everyday meanings and style choices.

"Context and stated intent should guide how the label is used."

In practice, good definitions remain flexible. Pair a short definition with examples and artist statements so readers can see how words map onto actual work.

Conclusion

To sum up, definitions gain value when paired with examples and museum context.

Clear language helps readers track a long history from 19th‑century studios through the Harlem Renaissance, WPA programs, and the Black Arts Movement’s cultural power.

Museums in new york and coverage by the new york times shape how visitors read labels and collections day after day. Good practice names themes, methods, and references instead of relying solely on an artist’s biography.

Seek collection highlights, public works, and focused shows to see continuity across generations. Learn more about the movement’s aims and legacy at this Black Arts Movement overview.

Enhance Your Space with Unique Modern Masterpieces by Chiara Rossetti

Are you inspired by the innovative mediums and conceptual depth highlighted in our exploration of contemporary art? You’re not alone! Today’s art enthusiasts are seeking cultural relevance and emotional connections in their artwork. However, finding pieces that resonate with modern themes and fit your unique style can be a challenge. That’s where we come in!

At Rossetti Art, we specialize in canvas prints, original paintings, and modern sculptures that celebrate the spirit of now. Each piece created by Chiara Rossetti brings a personal touch that connects deeply with current social narratives—just like the modern masterpieces discussed in the article. Don’t miss out on the chance to elevate your home decor with breathtaking artwork that speaks to your values and aesthetic. Explore our collection today and find your perfect piece! Act now, and transform your space into a gallery of inspiration!

FAQ

What is the definition and common examples?

A shorthand for creative work rooted in the experiences, histories, and cultures of African-descended communities. Examples include Harlem Renaissance paintings, WPA-era community murals, contemporary installations by artists in New York museums, and prints or quilts that center Black life and memory.

How does the glossary definition differ from a simple label?

The term can name subject matter, not only the maker’s identity. It points to themes, styles, and social contexts—narratives about race, resilience, and diaspora—rather than serving solely as a demographic tag.

Which related terms appear in discussions and scholarship?

African-American art, the Black Arts Movement, diaspora art, and community-centered practices. Critics and curators often use these alongside museum classifications and exhibition texts in places such as the New York art scene and national collections.

How has the meaning evolved in the United States?

The phrase expanded from early 20th-century cultural renaissances through mid-century social realism to later political movements. Each era added layers—formal innovation, community advocacy, and explicit political purpose—that shape today’s usage.

Who were early figures that shaped the field?

Artists such as Edward Mitchell Bannister, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Henry Ossawa Tanner, and Edmonia Lewis created visible precedents. Their work helped form institutions and audiences that later supported broader movements.

What role did the WPA and the Black Arts Movement play?

The WPA funded public works that brought Black subjects into civic spaces. The Black Arts Movement connected aesthetic practice with political organizing, encouraging artists to foreground Black experiences and community needs.

How do curators and major outlets influence the term?

Curators, museums, and media outlets like the New York Times shape public understanding through exhibition choices, labeling, and reviews. Institutional framing decides which narratives gain prominence and which collections enter the canon.

What styles and themes are commonly associated?

Social realism, folk traditions, abstraction, conceptual protest art, and work engaging history, memory, and identity. Themes often include migration, labor, family, resistance, and diasporic connections.

Which sculptors and painters are central to study and collections?

Notable sculptors include Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Augusta Savage, and Richard Hunt. Painters and printmakers of note include Henry Ossawa Tanner, Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold, and Elizabeth Catlett—artists frequently featured in museum collections and academic syllabi.

Who represents conceptual and political practice?

Figures such as Emory Douglas and Fred Wilson exemplify art that interrogates power and institutions. Contemporary curators and galleries continue to highlight diasporic voices and politically engaged exhibitions.

How do dictionaries and art history texts treat the phrase?

Reference works often list multiple senses: an entry may describe artistic production by Black creators, works about Black life, or movements with political aims. Context in catalogs and essays determines which sense applies.

Where can readers see authoritative collections or shows?

Major institutions—the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Brooklyn Museum, the Studio Museum in Harlem—and rotating shows reviewed by outlets like the New York Times provide accessible examples and scholarship.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.